I have been kicking around the idea of a long voyage on the Loire River in France for a while. Spend a month or two speaking and reading nothing but French, get to know the homeland of my wife and children a little better, eat some good food, drink some good wine, learn a little history, check out the wildlife, and see a whole lot of one of the most beautiful rivers on our green Earth.

Happily, Garth Battista at Breakaway Books, no doubt suffering from a bout of cabin fever up there in his snowy mountain aerie, was also very much taken by the idea. So, unless he comes to his senses pretty soon, it looks like we are going to do another book together.

|

Source of the Loire circled in red. Red line is the estimated extent of navigability in a small boat not captained by an insane person. Map from 1685 by Sebastian Munster.

click thumbnail images for larger view |

So what kind of boat would one use for such a trip? It would be about 400 miles from the beginning of navigability to the sea at Nantes. The Loire is, almost uniquely for a big river in Europe, still relatively wild for long stretches of its course. Braided channels, long stretches of easy water, here and there dams that must be portaged, and rapids and riffles that could be run in a handy little boat. The obvious choice would be a canoe or kayak. Agile in tight spots, easy to portage, and having the benefit of being the simplest of boats.

But I have made some long trips in canoes, and there are drawbacks: finding a camping place at the end of the day (or too much earlier - should I stop there, or hope to find something downstream in the next hour or two?); camping through stretches of bad weather can be a chore; it is very hard to keep a dry canoe, and the water that gets in seems inevitably to find its way into the “watertight” packs one uses. Since I am going to do a book, it will be important to have a dry, relatively airy place to keep a couple of cameras, and maybe even a laptop computer.

There is also the consideration that I would need to leave the boat for hours or a day at a time to make side trips, and having a boat that could be locked up and chained to a quay someplace public without having to worry too much about theft was also a big plus, as was the possibility of carrying a small bicycle for increased mobility on dry land. The idea of being able to chuck an anchor over the bow, or tie a line to a tree, and step into a dry, comfortable, if tiny, space, and go to bed or sit out a stretch of bad weather is very enticing. I also want to be able to build a removable bunk maybe 4 inches off the floor to help keep the bedding clean and dry on what could be a pretty mucky trip in places. It was clear I should be thinking of a more substantial boat.

What I was looking for then was a boat with a very shallow draft, wide and long enough for a cabin big enough to have a real bed, sitting head room, but not too big to be to be relatively easily driven by pole and oar and sail. After looking around a bit, I found Jim Michalak’s AF3, and after a couple of e-mails with him, thought maybe I had found my boat. A decent-sized cabin with a top that could be raised a bit to provide good sitting head room, easy to build, a couple of inches draft, and a proven design.

“There is a special gaze, a sort of hypnotized stare, that men develop as they look at the sail plan or line drawing of a possible boat. It isn’t really an examination or analysis, but more of a giving-up of the beholder to the object beheld -- a semi-mystical act, producing little that is concrete and especially annoying to people like wives, who speak to you and receive no answer.” -- Anthony Bailey, The Thousand Dollar Yacht. The model is scaled 1cm - 10 cm: I love working in the metric system, it is just so easy to use. |

|

But one problem is that there are at least four dams on the Loire. Even with the help of a little cart, could I reasonably expect to horse the AF3’s 250 pounds (minimum) out of the water and then over a portage that might not always be a solid, paved surface? I planned to bring a come-along and a couple of hundred feet of light rope with me, and certainly if I was willing to wait, somebody would probably come along to give me a hand. But then I also spoke with Rob Rhode-Szudy who pointed out that the windage on a boat like the AF3 was going to make it hard to control while rowing or poling with any wind forward, especially given that I was planning to increase the height of the cabin top by about 6 inches to get a little more head room.

Making the boat lighter than an AF3, which is about as light as you can easily go, I would think, in terms of build, is in principle easy: just make the boat smaller. In my case this would have amounted to cutting off the nose to make a pram bow, and at that point I could see Jim Michalak reading this and thinking, “Sure, take my design, build up the cabin top, cut off the bow, who knows what else when saw meets wood,” and running screaming out into the night. So I knew that I was just going to have to do my own boat. John Welsford’s Tread Lightly was also a touch point, in terms of the size, and layout of the cabin and cockpit etc.

But the windage? It was clear I needed to think of a different kind of boat. Rob was talking up the Pole Punt, and Chuck and Sandra Leinweber had pretty good luck with the River Runner on a long river trip. So those might be a good place to start thinking, but what about the cabin I wanted? Then occurred to me that I could simply make the cabin so that could be raised and lowered on the boat, and even removed to cut that much weight during portages.

|

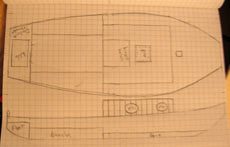

Model drawing, one square equals 10 cm. |

So out came the graph paper. I figured on a length of 4 meters (13 ft), because that was what Tread Lightly came out to. A beam of 150 cm (5 feet, it narrows to something like 140 cm because of the angle of the sides) because that was the minimum I figured I could put up with in a cabin that had to be liveable, though I hope to be able to cut this down a little, maybe to 140 cm/130 cm, which will save a little weight and make the boat easier to push through the water.

So the boat that emerged, not coincidentally I suppose, was basically a traditional, if tiny, Loire River barge, decked over in front, with a tiny cabin. It was also a boat, not coincidentally, very like the one I had drawn in my head when I first started thinking of this voyage a year or two ago, before I told myself, “Don’t be an idiot, and try to reinvent the wheel, buy some plans and build the boat.”

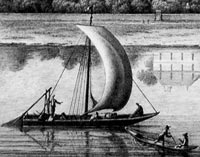

A “futreau,” a kind of flat bottomed sailing scow, almost always square rigged. |

|

|

First look at the hull form I had sketched out. |

The basic hull form after a little tweaking. |

|

|

Add chine logs, bottom, rub rails, mask off the parts to remain bright, and recruit some help for staining the hull. Of course the nicest thing about this kind of three-dimensional thinking is that at the end of it, you have a nice toy for the kids, too. So much the better if the munchkins had a hand in the making. Maia was in the remains of her tiger makeup from Cologne’s Carnival (Mardi Gras) festival. |

Cabin up. The portholes are the male sides of some heavy brass sail grommets I had tucked away. I clipped little flanges in the end of the tube that normally extends through the cloth, and then held the grommet in place and bent the tabs over inside the cabin with a screwdriver. |

|

The main question was the cabin top. How high could it be extended in relation to the height of the topsides. I figured 100 -105cm would do me well enough, and as drawn the boat was about 40 cm deep and in the model I increased that to 50. So there would be easily 40 cm available for cabin sides hidden below deck underway, plus say 30 cm minimum sticking up above deck at all times. So that makes 70 cm cabin sides, plus the 40 - 50 cm deep hull, which comes out to at least 110 - 120 cm (3.8 to 4.2 feet). Plenty of room to work with. On the model, the cabin top ended up being 11 cm high, with another 1 cm fudge room.

With this “dry” cabin that rises up and down, how was I going to prevent water from pouring through the gap between the cabin sides and the deck? Well I figure I can build a coaming around the hole in the deck in 2x2 cm ( 3/4” x3/4”) Then on the cabin sides, glue and screw another one, slightly wider, so that when the cabin is down, its weight rests on the coaming, and then figure out a way to lock it in place, (old fashioned sash window latches? or dead bolts?) and put a piece of closed-cell foam gasket between the two pieces of wood to make the joint more or less water tight. That is pretty doable I think, but I am not sure how to seal the joint with the cabin raised. I think the best bet is to glue a strip of polyester-reinforced pvc cloth around the level of the cabin that will stick up above deck and fix it with a brass batten. With the cabin raised, the skirt can be feathered out beyond the deck coaming at a good downward angle, and the cabin locked in place there. So any rain will run down the cabin sides, onto the pvc cloth, and off onto the deck. The PVC cloth and batten should only need a clearance of maybe 4 millimeters, tight enough to be workable, and the cloth is stiff enough to provide a good slope and a good drip edge.

The other trick is that I am going to have to build the cabin as a slot top to be able to get forward, especially if I rig her for sail. Making the door watertight is going to be a trick, too.

|

Sail brailed up to raise the cabin. I stitched up the sail out of some Sunbrella fabric I had left over from another project. |

For the model I made a gaff rig. But for the actual boat, I am not sure what I will do. My head tells me that for this trip, a sail will get in the way more than anything else. On the other hand, for me a boat without a sail is kind of half a boat. If I rig the boat for a sail though, I will no doubt see the error of my ways.

The traditional boats on the Loire, even the tiny ones like this one, often carry a very tall, narrow square rig. But I suspect they do not carry them under most of the bridges, more than once anyway, and a tiny, light, boat like this is not going to be able to stand up to a tall rig: I would guess that a traditionally built boat, with 1” oak sides and 1 1/2” bottom would weigh at least 8 times what my boat will, and they don’t normally have cabins that interfere with sail handling. On the other hand, a boom would come in handy raising and lowering the cabin. So I guess if I carry anything it will be a gunter rig. I have been thinking of a relatively small sail, for off- and down-wind work mostly. In any case I will add a lee board to help with tracking. They say “Gentlemen don’t sail to windward,” so with this boat, I may yet join that select group.

Le Fou du Bois (crazy man of the forest) on the Loire. A small “chaland” made by Hoel and Ninon Jacquin near Tours, France. The mast is very tall and carries a relatively narrow square sail. The idea is to be able to get some canvas up into cleaner air above the riverbanks. |

|

|

I like the lines. I used wood screws to clamp the deck and the rub rails on the boat, and rather than leaving them or filling the holes, I pulled the screws once the glue had cured, and tapped in some small copper nails to cover the holes. All and all she is about as stomp-proof as this kind of toy can get. The other day I found the youngest with one foot on the cabintop and the other on the fore deck holding the mast and trying to use the boat as a pogo stick. Yikes! But no problems. |

A little scale. The pencil is 19 cm long. I am 183 cm tall. So I would be, to scale, a little shorter than this pencil. Not a whole lot of elbow room, or foot room either but workable, I think. |

|

|

Standing up in the cockpit. |

Piglet could have used this one on his Blustery Day. |

|

The big question was how much would this all weigh? I was looking through the February 2008 edition of Woodenboat, and stumbled on the Bay Skiff 15, which is a sort of medium-built boat in 9 mm ply with a fair amount of 3/4” hardwood seating that tips the scales at 150 pounds. A little longer, but a little narrower. So I figure that with sides in 6 mm plywood and a bottom in 9 mm, my boat, with glass/epoxy sheathing, and without the removable cabin, should weigh at most the same.

The other option I was thinking of was to build in solid wood: a sort of traditional planking-strip planking hybrid in 9 mm spruce wainscotting that they have stacks of, very cheap, at the big box near the in-laws’ in France. The boards are tounge-and-groove. Doing the math: each side, 50 cm x 4 meters, would be 2 square meters. The bottom worked out to about 4.5 square meters. So double the sides and double the bottom to take framing and glassing into account, and it comes out to about 13 square meters of spruce, say, 1 cm thick. Add another square meter for luck, and you are at 14 square meters, or .14 cubic meters. Spruce weighs in at about 450 kg per cubic meter. So that works out to 63 kgs, or 139 pounds. The detachable cabin would weigh maybe 30 pounds - easy to carry.

Not bad, in either case, and certainly horse-around-able. The other upside is that the roof rack on my van is rated to 75 kg, so the hull should be cartoppable, and the cabin will fit in the back of the van. Not something to pop on top and head off alone to the local reservoir with, but workable in terms of this trip at least.

The other big question is how much water would she draw? The Loire, like all wild rivers, has more than it’s share of shallows, and 2,000 years worth of building rubble under some of the bridges. Minimum draft is going to be key.

The bottom is roughly 4.5 square meters. The ends rise a bit though, so call it 4 square meters, or 40,000 square centimeters. The boat should weigh, all told, about 80 kilos. Add me, at 65, plus another, generous, 50 kilos for gear and stores, and that makes 195 kilos, call it 200 after a long lunch on shore. Handily, 1,000 cubic centimeters of water weighs a kilo. So it would take 40 kilos to sink the bottom of the boat, at 40,000 square cm, by one centimeter. At 200 kilos cruising weight, that works out to 5 cm, or 2 inches, draft. Another adult passenger at 70 kilos, or maybe a small barrel of wine, given the flare in the sides, and especially the increasing surface in the swept-up ends, would probably add another 1.5 to 2 cm draft. Not bad at all.

I have been doodling some ideas for a portable camp kitchen with a hinged front that opens down to be a cutting board/work surface, and a top that comes off to reveal a two-burner butane stove, with storage for dry goods, with a pot and frying pan in there too.

If Anthony Bailey was so entranced by a lines drawing, imagine what it is like with a 1-10 scale model in my hands... The girls seem to like her too. Right now she is full of fish-shaped plastic refrigerator magnets, so they have the right idea. Wonder what I should name her?

|

Loire River Festival in Orleans. |

|