|

BOATBUILDING WITH A DIFFERENCE IV

(For Aspiring Amateurs)

by Barend Migchelsen

Migchelsen@aol.com

https://ca.geocities.com/bmboats2002/

https://members.aol.com/_ht_a/migchelsen/myhomepage/

|

Barend Migchelsen, (pronounced Mikkelsen) learned to sail in The

Netherlands in 1943. In 1975 he started to build boats and boat models as

a hobby. Today, he organizes and teaches classroom courses in boat

building, and has published several books on the subject. The

following is an excerpt from one of these books.

Click here to check

out Barend's books at our store

|

|

In the

preceding articles I – III, the mathematical foundation of hard-chined,

small-boat design was shown. Once you digest the simple mathematics,

lofting becomes child's play. Little was said about the building process

itself.

THE CONVENTIONAL METHOD:

Upside

Down

For a “newbie” amateur one of the easiest ways to construct a hull is

the upside-down method: The cross frames, bow stem, and transom are placed

upside down on a building jig. The planks are hung around the frames. The

bottom closes up the hull box.

This method is exactly the same as for building the model except that the

jig is a ladder frame instead of a single 2"x3" “spine” as is shown in the

first photograph of article I.

THE BODY VIEW DRAWING IS THE MAIN

GUIDE FOR THIS METHOD!

After the hull is finished most amateur

builders have no further use for the building (ladder) jig. If it is

screwed together, it is easily taken apart. Completely eliminating the jig

is even more efficient.

THE THREE ALTERNATE METHODS

The

strongbox method

In the Body view of figure 4-1, a (red) horizontal line is

drawn between the Beam stations representing a deck. |

Fig. 4 – 1

The deck line is drawn in red

|

If the full-sized drawing is made on one-inch-grid graph paper, the

half-Breadth width of the deck at each station can be read off directly.

They are shown in the drawing.

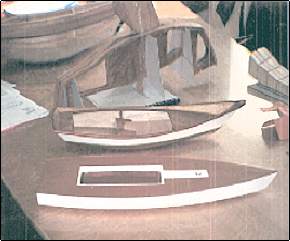

Plot the measurements on a plywood panel. Rip a 1"x2" at flare angle, glue

these inwale slats along the plotted points. Cut off the outside excess at

flare angle. See the photograph. A Japanese pull saw is ideal for this

exercise.

Placed on three sawhorses, the deck panel provides a perfect platform for

the rest of the hull construction without the need of a building jig.

Attach the carlings. Cut out the cockpit space as shown in the picture.

The cross strips are easily removed after the hull is finished.

Place the bulkheads fore of station line #4 and aft of station line #11 on

the platform. They are held plumb by a longitudinal bow frame fore of

station line #4 and a longitudinal transom frame aft of station #11. Next

is the (bottom) half frame at Beam.

My experience is that making notches in the inwales without cutting into

the deck and gluing the cross frames in these notches works a lot easier

and actually makes the setup stronger than notching the frames over the

inwales.

The 1"x1" linings on each side of the longitudinal frames take care of the

king planks and the keelson. The cross frames are lined all around in the

same way with 1˛x1˛ slats. The model frame in the photographs is mounted

on a 1"x2". |

| Sometimes, I hang the side panels first before the chines are placed.

The easiest way to attach the chines is on the outside, but IMO that makes

an ugly sight. |

Fig. 4 – 2 Three chine

solutions

This can be (partly) overcome by the compromise shown in the middle

drawing: a 1"x2" is ripped at flare angle and attached as shown.

Personally, I prefer the chines on the inside.

After the hull is turned over, if you leave the sides as they are, you end

up with a very stiff, comfortable skiff. If you cut the side panels flush

with the deck you obtain a flat, Laser-type wet-sailer that will stand up

to rough treatment, and that is easy to car-top even if it is made from

low-cost, lightweight, 1/8" Lauan. |

| Make sure to seal the insides of the bow and transom (air) chambers

before placing the bottom. Plastic resin glue works well for this purpose.

IN THIS BUILDING METHOD THE HALF-BREADTH DRAWING OF THE

DECK

IS THE PRINCIPAL GUIDELINE!

You can’t go wrong with this method. All the correct bevel angles of

the cross frames are directly taken from the deck contour line.

The strongback-sandwich method

Howard I. Chapelle briefly mentions this method in his Old Testament of

the boat-builders' Bible "BOATBUILDING" (1941) on page 199, and

illustration #52.

A frame is made in the exact shape of the Profile view projection drawing.

THE PROFILE DRAWING IS THE MAIN GUIDE

FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE PROJECT!

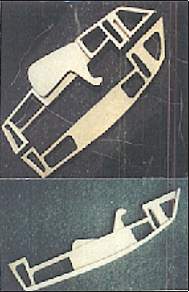

The

photograph at left shows such a frame for the San-Francisco Pelican. Two

panels of 1/8" Lauan separated by 1"x2" stock and lined on the outsides by

1"x1" works fast and easy. Remove the excess plywood after the frame is

put together. It makes a lightweight, strong "spine" that stands on its

own even before the cross frames are attached. The

photograph at left shows such a frame for the San-Francisco Pelican. Two

panels of 1/8" Lauan separated by 1"x2" stock and lined on the outsides by

1"x1" works fast and easy. Remove the excess plywood after the frame is

put together. It makes a lightweight, strong "spine" that stands on its

own even before the cross frames are attached.

It is not necessary to build all the full-sized hulls to obtain the

insight and the experience. A to (1/6) scale model made from 2-mm

cardboard will do. Actually, making a model of this low-cost material is

slightly more difficult than the real "McCoy" because of the smaller

tolerances and the cheap quality of the material.

|

The "third" alternate method

I call it by that name because I can't think of a better name.

If you have tried all the methods mentioned before, you are no longer a

beginning amateur but you have become familiar with the measurements. You

have gained a lot of insight in the lines and the proportions of a hull.

In this method, you assemble a centerboard box and attach the bulkhead at

station #4 and the cross frame at station #8. This is the building jig.

Cut the side panels. Attach the panels to the bow stem. Place the panels

on the setup. Line up station line #4 and #8 (Beam) of the panels on the

bulkhead (#4) and the (half) cross frame (#8). Hold the side in position

with clamps. Bring the panels aft together with a Spanish windlass to

attach the transom.

It is the simplest method as long as you know what you are doing, |

The beauty of trying all these methods is that you can do it on the

kitchen table during the (too) long North American winter season. It shows

you exactly how to prepare the parts of your hull in kit form. It will

give you a head start on the (too short) summertime.

Sheers and Chines, Barend. |

Back

to Part 3

On to Part 5

|